Senegal was

declared ebola-free in mid-October, just before a similar declaration for Nigeria. Having previously looked at

languages and communication in Nigeria's success, this post will do the same (belatedly) for Senegal. Language is a key consideration in ebola messaging in the multilingual states of West Africa, even if that fact is sometimes overlooked (such as by a

National Geographic article on four lessons from Nigeria and Senegal, or a

US Embassy Dakar sponsored conference for journalists on responsible ebola reporting).

By way of background, French is the

official language of Senegal, and

Wolof the most widely spoken. Of

the country's 38 languages (by

Ethnologue's count). Wolof and five other languages -

Jola (

Diola in French spelling),

Malinke,

Pulaar (as Fula is known there),

Serer, and

Soninke - are the main

national languages. I'll return below to more detailed discussion of categorizating indigenous languages in Senegal, as it could be relevant to planning messaging strategies in similar multilingual countries like Mali, which is the latest country in the region to have an ebola crisis.

Enter, ebola

Prior to the sole ebola case in the Senegal - an infected man who came from Guinea to Dakar before

the closing of the Guinea-Senegal border on August 21 (he ultimately recovered) - the country had been "

well-prepared with an Ebola response plan as early as March." From what information I've been able to gather, information and public education aspects of this plan used a number of languages, but mainly Wolof and French. (An

earlier posting included some links to videos and other web-based info in Wolof and Fula/Pulaar.)

A Senegalese source I consulted (

Dr. Ibra Sene) indicated that Wolof and French were

used in various media as part of the "massive campaign" to educate

people about ebola. However,

a report in International Business Times (25 September), characterized radio and television broadcasts of ebola prevention messages as "all day long, in all languages" (without specifying which). If the latter is accurate, it is likely that local

community radio stations extended the campaign in additional languages (more on community radio below).

Still, an

SIL-led initiative for translation in southern Senegal was a response to the perception of insufficient attention to communicating about ebola in less-widely spoken languages. It focused on developing ebola materials in the

Bandial Gusilay, Jola (Jola-Fonyi), and

Manjaku languages of Casamance. Two expat literacy workers in Senegal who facilitated the workshop,

Clare Orr and Elisabeth Gerger, framed it this way

"These days, a lot of awareness-raising about Ebola is going on across Senegal on the radio and TV. However, many people in the villages don't speak enough French, Senegal's official language, or Wolof, the most widely-used national language, to understand the message well. This is why we are trying to reach them through documents and information in their own languages. Those who are able to read in their language can always read the information aloud for those who can't."

Community radio

Community radio is a key component of development communication in much of Africa (see

here and

here, for example), including Senegal. A grant by

OSIWA in September to the Senegalese

Union des Radios Associatives et Communautaires (URAC) for an

ebola education program on 73 radio stations reflects the importance of this medium.

A couple of articles have highlighted community radio broadcasts about ebola in first languages of other countries -

Guinea, and

Liberia and West Africa in general - so one may assume that something similar has been happening in on community radio stations in Senegal. Questions relating to African language broadcasts about ebola on community radio include: which languages?; how was the material developed/translated?; and is any of it available in recordings or transcriptions?

An interesting dimension of communication via local radio in West Africa is that of associated radio listeners' clubs. The UN FAO

noted use of these (and a training for club leaders) to address ebola in communities in Senegal.

Social media

On social media, an interesting initiative launched at the end of August as a Facebook group called

SenStopEbola, with an associated Twitter account

@senstopebola,

translated notices and advice on ebola into seven Senegalese languages (see also

here; the languages were not specified, but presumably included French and the 6 main national languages). .

Senegal made use of SMS to send

text messages about ebola, but reports I've seen have not indicated what languages were used or the content of messages. Also, it's not clear whether the multilingual GooglePlay app - "

About Ebola" (which was created last April, and mentioned in a

previous posting on this blog) - is counted as part of this effort. Another GooglePlay app,

SenStopEbola, which is evidently related to the initiative on Facebook, was

mentioned as having Wolof content, but again, no information on how it has figured in wider efforts.

The national languages of Senegal

Of the 38 languages of Senegal, the six most widely spoken - Wolof, Pulaar, Seser, Soninke, Malinke, and Jola - were denoted "national languages" first by

presidential decree in 1971, and are specifically named as such in the

Senegalese constitution of 2001. The constitution allows for other national languages once "codified" (which includes establishing an "official" standardized orthography).

From 2001, the policy has been to

expand the number of national languages, and to that end, several others were

codified by 2002:

Hassaniya Arabic;

Balanta;

Bassari (a.k.a. Oniyan); Manjaku;

Mankanya;

Noon; and

Saafi (a.k.a. Safen). Codification of others has apparently proceeded since then.

The result is

three "groups" of Senegalese languages that reflect history and number of speakers (without implying a hierarchy of value):

- Those recognized early as national languages, which tend to have the largest numbers of speakers, and for which there is some notable amount of written material.

- Those codified more recently, but which still need further research

- Those still needing further study towards codification.

Such a grouping of languages in a multilingual state might be a useful parameter to consider when planning out messaging on health topics such as ebola, or other development communication. The first group is readily used, with standard orthography, perhaps also having resources available to consult on the subject area involved - and it reaches the largest number of people. It may be possible even to work on materials outside of the country. The second group may require more effort, including consultation with experts in country. The third may require work mainly on the local level, and where there is not time to develop a standard orthography, use of phonetic transcriptions.

The experience in Senegal may have followed the above to a degree, but further information is needed. In any event, the first group is divided between Wolof, which was widely used, and the other 5 established national languages, which presumably had varying use (ebola info in Pulaar was on the web, for instance, and the others were probably used on community radio).

Spelling again

As a small contribution to review of ebola materials, the ebola poster in Wolof above has one apparent misspelling - "

Fagaroul" - with the French "ou" taking the place of the Wolof "u." It is interesting to note, however, that the same title and spelling is used on the

French version of the poster (i.e., a Wolof title, with French influenced spelling, on a French language ebola poster).

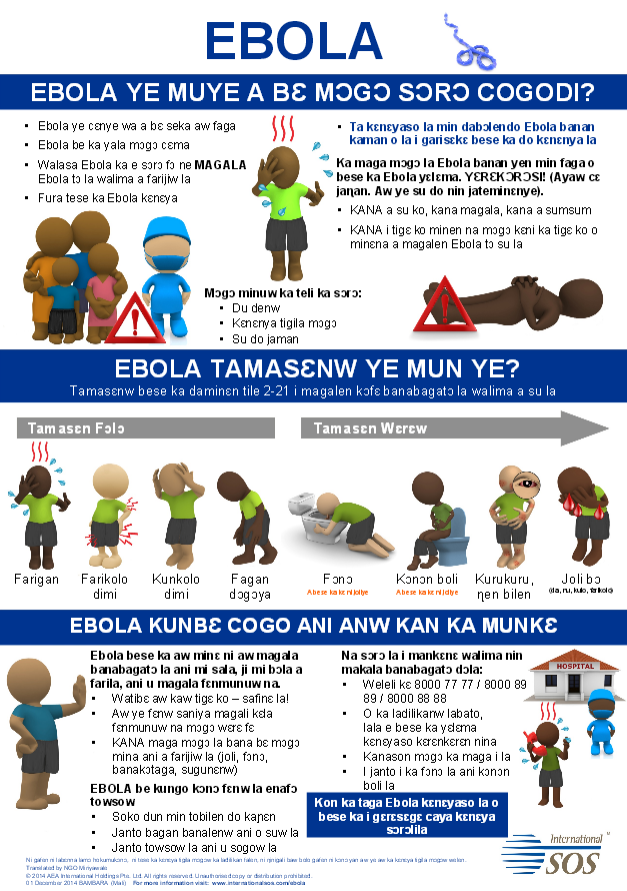

An earlier post looked at problems with non-standard Bambara in an ebola poster. Here I'll look at similar issues with a poster in Malinke (Maninka), a closely related Manding language spoken mainly in upper Guinea, and also southwestern Mali.

An earlier post looked at problems with non-standard Bambara in an ebola poster. Here I'll look at similar issues with a poster in Malinke (Maninka), a closely related Manding language spoken mainly in upper Guinea, and also southwestern Mali.